Three College of Law alumni took on racial injustice in Memphis, and their efforts have forever impacted the city.

Wednesday, Dec. 20, 2017

Van Turner stood in the cold, his hands in his pockets as he tried to stave off the chill.

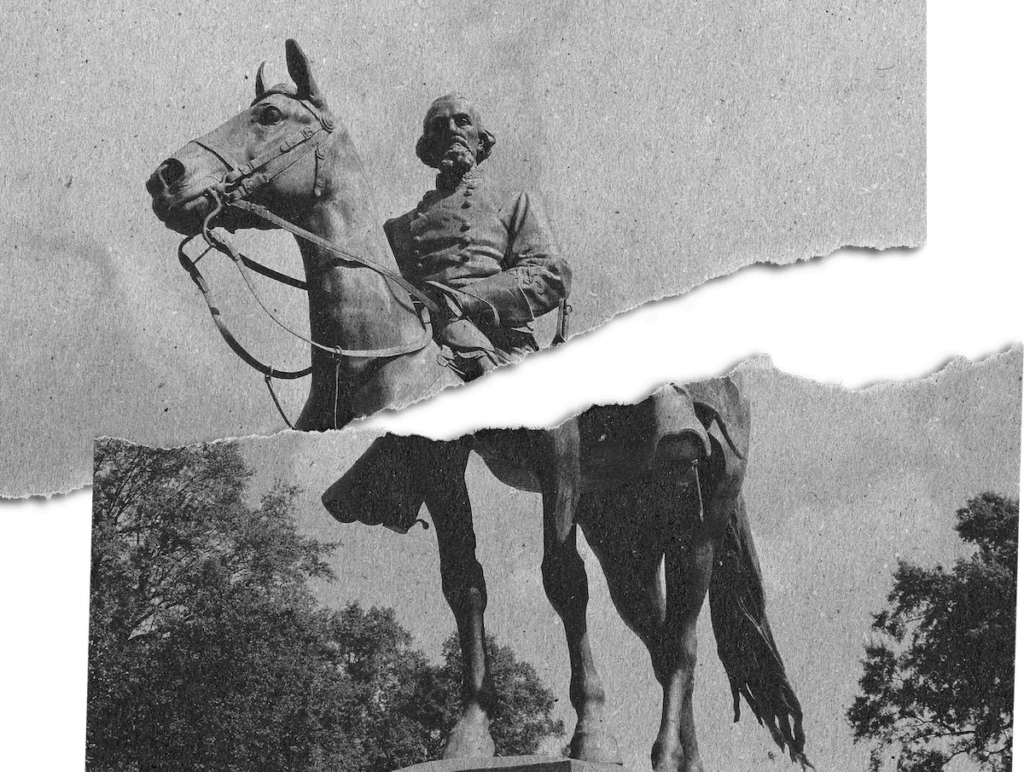

Yellow police tape signaled onlookers to keep their distance while the flashing blue lights from police cars sliced circles through the dark. Television reporters stood nearby as helicopters circled overhead, their cameras affixed on a dimly lit bronze sculpture standing 21 feet tall. The sculpture, synonymous with Memphis and depicting a scowling goateed soldier astride his muscled horse, held its place in one of the city’s public parks for more than 116 years.

As he tried in vain to hide his nervous energy, Turner watched workers struggle positioning their crane and its heavy straps around the statue to pull it from its marble base.

Two hours later, as the weight of the massive replica of Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest was lifted from its base in Health Sciences Park, Turner stood quietly while his emotions reeled from the realization of what had taken place.

The former Ku Klu Klan leader’s likeness would no longer mark the city. It would no longer stand as a symbol of oppression, hatred and racism that taunted black residents. Turner realized in that moment that his efforts would impact generations to come.

Turner’s work to remove monuments honoring Forrest, Confederate Army Capt. J. Harvey Mathes, and Confederate President Jefferson Davis from Memphis parks was a hard-fought battle.

The removal, which came on the heels of violent protests against confederate memorials in Baltimore, New Orleans and Charlottesville, Virginia, seemed to be a quick response to the outrage of the day. But it had, in fact, been was more than three years in the making.

Van Turner

Memphis City Council attorney and College of Law alumnus Allan Wade (‘75) set the wheels in motion in early 2013, drafting an ordinance to change the names of three Memphis City Parks. The nine-member council voted unanimously to support it in advance of the Tennessee legislature’s passing of the Tennessee Historical Protection Act that now prohibits local governments from changing park names or removing monuments that honor wars and war heroes.

With that council vote, Confederate Park became Memphis Park; Jefferson Davis Park became Mississippi River Park; and Nathan Bedford Forrest Park became Health Sciences Park. Council members at the time said the name changes were a step toward helping the city, where 63 percent of the population is black, overcome its racist past and unwelcoming reputation.

After the park name changes were implemented, the real legal maneuvering began, former Memphis City Attorney Bruce McMullen said.

Former City Councilman Jim Strickland had waged a successful campaign for mayor and appointed McMullen city attorney. Both prioritized moving beyond renaming the parks to removing the sizable confederate statues that remained in two of them.

"We didn't want Memphis to become a flashpoint for protests when we were planning Martin Luther King celebrations throughout the city."

Bruce McMullen

The city pressed its case with the Tennessee Historical Commission to remove the statues in advance of the Memphis celebrations to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the death of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr.

“We didn’t want Memphis to become a flashpoint for protests when we were planning Martin Luther King celebrations throughout this city and were likely to be featured on a national stage,” McMullen said. “We hoped to get dignitaries like Barack Obama in Memphis. We didn’t want those statues to be a distraction.”

When the Tennessee Historical Commission refused the city’s request to remove the statues, McMullen proposed an alternative solution. He could sell the parks to a nonprofit entity that could operate without the burden of the state’s restrictions.

“We were looking around for a non-profit that would align with our interests, and that was our quandary,” McMullen said. “In talking to them, none of them had an appetite to buy a lawsuit that was sure to come. We knew we needed someone who could handle the publicity and the lawsuit.”

Bruce McMullen

It was at a Memphis Grizzlies basketball game where McMullen coincidentally bumped into Turner. The two men, friends through their common bond to the UT College of Law, agreed to meet the next week for breakfast at the Westin Hotel. During their meal together, McMullen (’96) suggested to Turner (’02) that he create a non-profit to purchase the parks.

“Van said right away that he would do it, and I was a little surprised,” McMullen said. “I said ‘Hold on, you need to talk to your wife, because this could get dangerous.’

Van called me the next day and said he was in, and the Memphis Greenspace non-profit was created.”

At a Memphis City Council meeting on Dec. 20, 2017, council members voted unanimously to sell Health Science Park and its easement on Fourth Bluff Park for $1,000 each to Memphis Greenspace, Inc.

After the vote, Mayor Strickland shared the news on social media and announced that the statues were being removed that evening by a private company. Memphis police positioned themselves at the park entrances placing yellow tape to halt traffic flow. Turner had arranged for a crane to remove the Forrest statue first at around 6 p.m.

At the time, the public was unaware of the relationship between Wade, McMullen and Turner. No one was aware of the effort over several years to find shortcomings in local and state laws that would lead to the sale of the public parks. No one was aware of Turner’s quiet fundraising that enabled a newly established non-profit to purchase two parks and pay a company to move the statues to a private storage facility within hours after the land transfer was complete.

They were only aware that the statues were coming down.

“We had to keep everything very confidential because we were afraid if it got out the Sons of the Confederate Veterans would run to court to get an injunction to stop us,” Turner said. “A lot of luck went into this. At any time it could have been derailed, but it was not.”

McMullen considers it a defining moment of his legal career.

“I feel really proud,” he said. “It was so much fun to see an endpoint that was so far away and so remote, and to know that all of the pieces that had to fall together over a period of time.”

The removal of the statues wasn’t the end of the controversy over the Confederate landmarks in Memphis. Sons of the Confederate Veterans filed petitions with the Tennessee Historical Commission and the Davidson County Chancery Court alleging fraud, conspiracy and desecration of graves, and seeking to invalidate the sale and return the statues.

Their complaints were unsuccessful.

The park that housed the statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest was also the gravesite for the Confederate general and his wife and had been since 1904. Late last year, lawyers for Greenspace and Forrest’s remaining descendants filed court documents expressing joint interest in the bodies being transferred to the Sons of the Confederate Veterans. The group plans to move the remains to the National Confederate Museum at Elm Springs, in Columbia, Tennessee.

Memphis Greenspace still owns the parks and continues to maintain them. Old picnic tables and benches were replaced over the summer, and new concrete paths were poured to correct longstanding drainage issues.

In January 2020, Turner, McMullen and Wade received Luminary Awards from the City of Memphis for their “tireless work over the course of their careers to improve the quality of life for Memphians.”

Turner said he’s proud to have stood beside two fellow UT College of Law graduates to work through the legal maneuvering that was required to bring change about in Memphis. It’s also bittersweet, he says, to think that his non-profit owns the park that his father was once forbidden to enter.

“My dad grew up in the Jim Crow-era in Memphis. There were only certain days when blacks could visit the zoo,” Turner said.

Allan Wade, Jim Strickland, Van Turner and Bruce McMullen (Submitted photo).

“When he was a child, he couldn’t walk through Forrest Park unless he was accompanied by a white person. It left a hole in his heart.”

“To take that monument down, we corrected a wrong, and my first call was to him when that monument came down,” Turner said. “I told him ‘Hey Pops, we got it done.’”

This story was originally appeared in the Spring 2021 edition of Tennessee Law, the alumni magazine of the University of Tennessee College of Law.